July 26, 2024

That wood is pleasant sounds rather self-evident. We probably think of a mighty tree in a restaurant garden in the middle of summer, and if given a choice, we definitely prefer to sit under the tree than under an umbrella. Trees give off good shade, as we like to say in Slovenia. But there seems to be much more.

Dr Michael Burnard, researcher, lecturer at the University of Primorska and Deputy Director of the InnoRenew CoE, studies the effect of wood on the well-being and health of people.

Dr Burnard has long been interested and involved in the forest sector. In Oregon (USA), where he comes from, Mike worked at an innovative lumber company, originally founded by his grandfather, until pursuing a graduate degree at Oregon State University, where he completed his Master of Science in wood science. He obtained his PhD at the University of Primorska in Koper. It was during his doctoral work that he began to study the effects of the built environment on human health, selecting the effect of wood on the well-being of people as his thesis topic. He continues to build upon this research and his findings at the InnoRenew CoE.

As he explains, scientists have studied the effects of wood in the built environment on human health, largely examining the impact of air quality, but only a handful of studies have explored the effects of wood on well-being from a holistic approach.

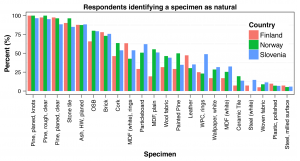

In their early research, Dr Burnard and his colleagues focused on the perception of materials (Building material naturalness: Perceptions from Finland, Norway and Slovenia) to establish the degree to which people identify them as natural by observation alone. Their survey involved approximately 200 people from Slovenia, Norway, and Finland. In Slovenia, two groups (from Koper and Ljubljana, respectively) participated.

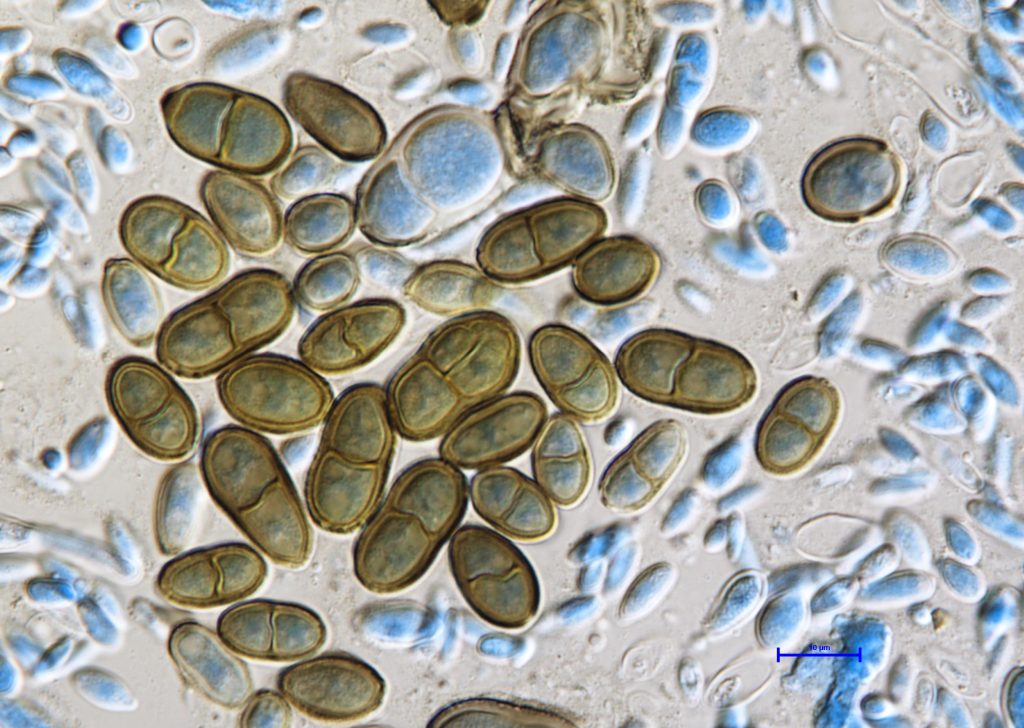

The respondents were asked to observe, but not touch, 22 building materials, including solid wood, engineered wood-based products, masonry, stone, wallpaper, ceramic tiles, metal, and plastic, and answer three questions:

The material perceived as most natural was planed knotty pine, followed by rough clear pine (in Ljubljana, the order was reversed, but the difference was negligible), planed clear pine, stone tile, and planed ash heartwood. The groups in Ljubljana and Koper, unlike the Norwegians and Finns, ranked stone tile fifth.

The specimens ranking highest on the scale (from left to right): clear pine, rough; knotty pine, planed; clear pine, planed; stone tile; ash heartwood, planed.

There were no major differences between the groups with regard to identifying the materials, but some variations were observed. Both Slovenian groups, for instance, ranked particle board and wood plastic composite (WPC) much higher than the other respondents, while the Finns ranked medium density fibreboard (MDF) significantly lower than the others. Such differences are likely due to the fact that knowledge of wood and wooden materials differs to some degree from country to country.

Specimens identified as natural (from left to right): knotty pine, planed; clear pine, rough sawn; clear pine, planed; stone tile, untreated; ash HW, planed; OSB; brick tile; cork; MDF, growth rings, white; particleboard; MDF, untreated; woven wool fabric; painted planed pine, white; leather, untreated; WPC, growth rings; wallpaper, white; painted MDF, white; ceramic tile, white; steel, painted white; woven fabric; plastic, polished; steel, milled surface.

According to Dr Burnard, the impression of naturalness is important for our life. In other words, what is around us has an impact as it rejuvenates our cognitive ability (the power of concentration, for example) and influences our response to stress. This hypothesis was confirmed in a follow-up study he conducted to determine whether wood can affect the experience of stress.

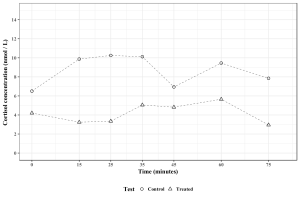

The study involved 60 people and was repeated twice. The tests took place in rooms with identical-looking desks, except that one was made of visible wood and the other was white (the sequence of rooms was random). In both rooms, the subject was seated in a comfortable office chair. Then, after a relaxing introduction, a screen showed a violent movie scene. In order to avoid showing the subjects something they have seen before, which would make the results less reliable, the excerpts were taken from different films, the thrillers Jason Bourne and Haywire.

“Wood” and “white” testing rooms

During the test, researchers measured the subjects’ heart rate and cortisol, a hormone that is one of the most reliable physiological indicators of stress. Cortisol levels in the “white” room were significantly greater than in the “wood” room. This finding is interesting as it indicates that introducing wood or other natural materials into our living surroundings – at home or at work – may reduce the experience of stress and, indirectly, its effects.

Cortisol concentration chart (∆: in “wood” room; О: in “white” room)

* * *

Dr Burnard says people in Oregon, much like Slovenians, appreciate the forests that surround them and utilize wood to enhance their day-to-day living, although there are some differences. For instance, many in Oregon do not appreciate the common “clear cut” logging method that produces the large quantities of wood used in their daily lives. Wood is the primary building material for around 95 percent of homes located in the United States, as opposed to Slovenia, where the percentage of wood used for home construction is negligible. In Dr Burnard’s view, the modest use of wood in Slovenian construction could be due to common misconceptions about wood as a building material, for example, the idea that concrete and steel are stronger and more durable.

The perception of wood in the construction industry has begun to change, however, globally and in Slovenia. To what extent and in what form wood could be more integrated into the everyday life of Slovenians – to achieve its maximum effects and benefits – will be determined in future studies.