April 17, 2024

In the middle of Koper’s historic urban core lies an abandoned and mostly overlooked building — an architectural gem holding an exceptional historic value. It rests upon the rock plateau overlooking the old harbor, and its roots can be traced back to the 12th century. In 1135, a small group of Benedictine monks settled by the church dedicated to St. Martin, forming a small monastic community. The Benedictines endured until 1380, when their community was destroyed during a violent attack by the Genovese who were at war with Venice.

It was decided to donate the damaged monastery to another monastic order in 1453 — the Servites. The former church of St. Martin is partly preserved in the central wing of the monastery, while the humble monastic buildings stood on its south side. The Servites first built a new cloister (with sculptural features typical of the Venetian 15th century) and, in 1521, started to build a big new church on the north side, which was completed in 1606. In the first half of the 18th century, the new church was connected to the monastery with two additional wings, forming a second inner courtyard. This is how the building presents itself today, including two inner courtyards, a large garden on the backside, the greatest surface area of any building in Koper’s city center and the only preserved monastery of the Servite Order in Slovenia, which grants it the status of a national monument.

The southern courtyard is partially enclosed by two wings of the monastery cloister (the north wing is shown in the photograph). Photo: Tim Mavrič

The monastery was the first to be abolished, in 1772, but the monks continued to live there until 1792. The Municipality of Koper wanted to move the former hospital of St. Nazarius from its original location near the Muda gate to the Servite monastery, but this action was delayed due to the political turmoil linked to Napoleon’s war campaigns. For a short time, the complex hosted a military hospital with the church serving as a prison. The public hospital finally settled there in 1810, and the church was retrofitted to host large wine cellars.

The building was used as a hospital throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. After the Second World War, the complex was converted to host the region’s central maternity home with associated pediatric and gynecological departments. The former church was turned into a furniture warehouse, which was destroyed by a fire in 1962 and replaced by the current kindergarten playground. The maternity home continued its operation until the late 20th century, becoming the “native house” of generations of local inhabitants and a place connected with numerous positive (personal and collective) memories. The maternity home and hospital departments finally moved out in 1996, and a methadone distribution center operated on the ground floor until 2003. Afterwards, the building was abandoned. The subsequent 17 years of decay have inflicted serious damage; however, this period was not entirely negative.

The abandoned building of the only preserved Servite monastery in Slovenia is located on Santorijeva street, upon the rock plateau overlooking the old harbour of Koper. Photo: Tim Mavrič

In 2011, archaeological excavations brought to light extraordinary finds. At several meters of depth, pieces of black and white mosaic patterns were discovered, covered by layers of plaster with color pigments (usually used for frescoes) and coupled with dispersed spots of hydrophobic plaster, usually used to build ancient roman hydraulic systems. Archaeologists have concluded that a prestigious Roman villa from the first century AD is probably hidden under the monastery. This find increases the value of the architectural complex considerably. Currently, InnoRenew CoE is engaging its technical team to assess the building thoroughly in order to determine the best approach for its renovation and future use.

Maintenance of a building’s overall material authenticity is a cornerstone of heritage conservation. For this reason, detailed documentation of the current state of listed buildings is of foremost importance. Good documentation allows accurate planning for renovation activities and insight into the building’s past state after renovation is completed, in case reversal of certain changes would turn out to be necessary. InnoRenew CoE is currently undertaking documentation activities in Koper’s Servite monastery by using one of the latest and most accurate tools available — a 3D scanner. This scanner is capable of recording an indoor or outdoor space to transform it into a digital 3D model.

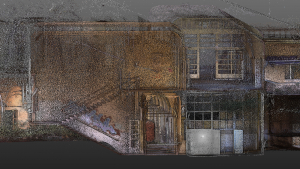

The 3D model enables a virtual walk inside the building. On the image from the black and white 3D model, a view from cloister to the entrance of the building. Source: InnoRenew CoE

3D scanner works through laser technology that detects distances of objects and surfaces from a selected station and a double rotating head that records the space in all directions. The result is a “point cloud” in a 3D digital coordinate system. By chaining a series of such 3D scans, it is possible to achieve an accurate digital 3D model of a building, which enables easy measurement of real distances and proportions and provides a base for construction of building information models (BIM).

In addition, the 3D scanner is also capable of producing high-resolution, 360-degree photos that further enhance its importance for the documentation process. Hence, 3D scanning is one of the most effective modern documentation techniques and improves upon the usual methods of photography, 2D architectural drawings and textual description. Currently, a detailed 3D model of Koper’s Servite monastery is being completed. Once done, it will enable the assessment of several building parameters, including material volumes and ceiling deformations.

The 3D model enables a look trough the building by adopting different views and cross-sections. Source: InnoRenew CoE

Sometimes information coming from documentation alone is not enough to plan renovation activities. Historic buildings have complex histories that result from centuries of enlargement and upgrading campaigns. A building’s history has to be thoroughly understood before renovation, but the marks of such history are usually hidden to the naked eye and have to be discovered. This building analysis or “bauforschung” practice usually uses invasive methods to reveal a building’s history. However, a number of new technologies allow non-invasive research. One such technique is thermography, carried out with the aid of thermal cameras.

Thermography allows preservationists to visualize the differences in construction materials’ thermal conductivity, which can also be used to detect hidden structures under layers of plaster on walls or elsewhere in historic buildings. Thermography has been applied to Koper’s Servite monastery in the past, but a further enquiry might be performed in the future. InnoRenew CoE owns a new high-performance and high-resolution thermal camera that could look deeper into the building’s structure and perhaps see what the older instrument could not. Overall, InnoRenew CoE’s work will not only contribute to the building’s renovation project but will also provide a full digitalization of the building, possibly enabling virtual reality tours for those who are interested.

Renovations of historic buildings are usually long processes that require careful planning, research, extensive documentation and lots of bureaucratic work due to the protected status, and every move has to be approved by the heritage conservation authorities. We hope that Koper’s Servite monastery will become a development node in the University of Primorska’s institutional framework. Where once children were born, new knowledge will spring to life.

Tim Mavrič,

assistant researcher at InnoRenew CoE

Source: Il convento dei Serviti. Un monumento architettonico e archeologico nel cuore di Capodistria. (ed. Neža ČEBRON LIPOVEC et. al.) Milano : Poliscript, 2017. https://www.fhs.upr.si/sl/resources/files//knjiznica/knjige/padriserviti81117ok.pdf (6.10.2020).